Ndrova, the Final Frontier

Ndrova, the Final Frontier

Check out Dr. Barord’s previous blog entries here:

Part 4 – Search for the Fuzzy Nautilus

Part 3 – Search for the Fuzzy Nautilus

Part 2 – Searching for the Fuzzy Nautilus-Blog from Dr. Greg Barord

Part 1 – Searching for the Fuzzy Nautilus – a Blog by Dr. Greg Barord

Arriving on Ndrova Island, Papua New Guinea gathering with the Mbunai tribe with research boats in the water. (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

After Kavieng, Peter, Rick, and I traveled to Ndrova Island in Manus Province, Papua New Guinea. We were also joined by Manuai Matawi (The Nature Conservancy), and Kanawi Pomat (Manus Provincial Fisheries Office). We were welcomed to the island by Chief Peter Kanawi and 20-25 members of the local Mbunai community. We were even joined by a few people that had worked with Peter and Dr. Bruce Saunders 31 years ago! Moving to a new research site means starting over from scratch.

Assembling the gear for the baited remote underwater video systems with the Mbunai tribe. (Photo by Peter Ward)

Thanks to the organization of Rick and Manuai prior to our arrival, we were able to get started working much sooner than we thought. But there was still a lot to do in a short amount of time. We all worked together to make final preparations and get the gear ready to deploy. On the first night, we planned to deploy both baited traps and baited remote underwater video systems, better known as BRUVS. We use baited traps to catch Allonautilus scrobiculatus, the fuzzy nautilus, so we can find out important information such as size, age, sex, and maturity. The BRUVS record how many nautiluses were attracted to our tasty bait, either raw chicken or tuna. The BRUVS also have an added benefit of recording behaviors, interactions with other species, and providing a glimpse into the deep sea habitat of Allonautilus, a habitat rarely studied.

Getting Started, Again

We loaded up our gear and crew into a couple small boats and headed to sea. We used a depth finder to make sure we were deploying our sampling equipment at about 300m (that’s almost 1000 feet!). Then we toss our baited traps and BRUVS off the boat. It’s always very exciting because this is the real ‘start’ of the trip. The scary part doesn’t come until the next morning when you hope that (1) your traps and BRUVS are still there, (2) your traps and BRUVS don’t get stuck on a rock, (4) your traps and BRUVS don’t get damaged, and (5) you actually catch something in the traps and record some good footage on the BRUVS.

After a restless night of worrying about our gear, we woke up to the sunrise at about 6:00AM. On Ndrova, the most important thing to remember every morning is to take your antimalarial pills because this region has some of the highest malaria cases in the world.

After breakfast and pills, along with a slathering of sunscreen, we headed out to sea to pull up our gear. It takes a lot of man power and time to pull up our traps. So, we were all pretty bummed when our traps had nothing in them. To top it off, our BRUVS had moved around on the bottom and tipped over so we also didn’t record anything. Definitely a disappointing first day but there’s always tomorrow. So it goes.

1st Allonautilus in 31 years!

Rick pulling out the 1st capture of Allonautilus scrobiculatus in more than 30 years. (Photo by Peter Ward)

On the second day, we set our gear a little shallower and tied them off to the reef below, rather than a surface buoy, hoping that this would keep our traps more stable (on one occasion, we tied them to a coconut tree on the beach). We made our BRUVS heavier and set them in an area without as much current, hoping that this would ensure the camera landed correctly and did not move. On the next morning (don’t forget that malaria pill), we caught Allonautilus and Nautilus (much older cousin) in our traps and also recorded both nautiluses with our BRUVS! SUCCESS!

Photograph of Allonautilus scrobiculatus as it is being released back to its deep sea habitat. The entire shell is covered with tiny epiphytes that give the appearance of fur. (Photo by Peter Ward)

Just from appearance, Allonautilus is as different as can be when compared to Nautilus. The ‘furry’ covering on the shell is the most striking difference along with a general yellowish-brown tint to the soft body parts. The fuzzy shell is actually made up of tiny epizoans, which are plants or animals (plants in this case) that grow on the surface of an animal. This furry covering may actually be a defensive adaptation to protect Allonautilus from octopus predation, as Peter suggested.

We Found Them. Now What?

Peter Ward holding the rare Allonautilus scrobiculatus that he last saw 31 years ago. (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

For each Allonautilus that we caught, we immediately placed them in a chilled aquarium on the boat. All nautiluses, especially Allonautilus, are sensitive to warm water (25-28 °C or 75-85 °F). because they usually live in cold water (15-19 °C or 50-60 °F). Next, we measured, weighed, sexed, and photographed each specimen. We also looked for scars on the shell and collected non-lethal genetic samples to help us determine how individuals and populations are related to one another. Once we collected our data, we released all of the nautiluses. Zero nautiluses are sacrificed.

1st Digital Images and Video of Allonautilus

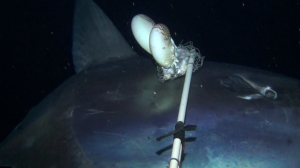

Throughout the South Pacific, we’ve deployed baited remote underwater video systems (BRUVS) to the deep sea habitat of nautiluses. We use BRUVS to estimate the population abundance of nautiluses and record additional information about behaviors, habitat, and other species of the deep sea. As soon as we got the BRUVS back to shore, we all crowded around the small camcorder and started looking at the footage. You never know what will pop up in the deep sea. From the amazing Allonautilus and Nautilus chowing down on our bait, to nautiluses mating, sharks swimming by, and even a sunfish (Mola mola) knocking a couple nautiluses off of our bait, the footage is priceless.

Snap shot of underwater video footage with Allonautilus and Nautilus feeding off of the same bait source in their natural habitat. (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

Snap shot of underwater video footage showing a sunfish, Mola mola banging into the bait stick with two Nautilus pompilius trying to eat. For scale, the sunfish is probably 1-2m across! (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

Snap shot of underwater video footage showing two Nautilus pompiius mating. The male and female grasp tentacles and may stay that way for hours as the male transfers a spermatophore. (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

1st Ever Tracking of Allonautilus

Greg releasing two Allonautilus scrobiculatus with ultrasonic transmitters attached to begin the 1st-ever tracking study of the species. (Photo by Peter Ward)

We also attached ultrasonic radio transmitters to three Allonautilus to track their daily movements. The transmitters relay information on the depth and temperature that Allonautilus is at every three seconds up to our boat on the surface. Tracking isn’t easy. We followed three Allonautilus, along with one Nautilus, 24 hours a day for seven total days. This was the first time that Allonautilus had ever been tracked! From the data, it looks like Allonautilus and Nautilus live at different depths, which might reduce competition for resources.

Packing Up

Our trip ended with our team literally collecting data as we were headed back to the mainland on the canoe with all of our gear. Peter was in a smaller boat following us, but still tracking the Allonautilus to the last second. Leaving is strange. Part of me is excited to get back to my family and friends and share our work. Another part of me is wondering if I’ll ever make it back to see and work with my new family and friends in Papua New Guinea. Chief Peter handed me a cowrie shell as a gift and a reminder of my time and Papua New Guinea and to not forget to come back. The sincerity at that moment, and the generosity during the entire trip, is something I will never forget.

Chief Peter holding the two nautiluses, Nautilus and Allonautilus, and seeing them alive for the first time. Chief Peter was instrumental in allowing our group to conduct the research in their waters and helping us every step of the way. (Photo by Peter Ward)

How Many Nautiluses are Left?

The shells of all nautiluses (Allonautilus and Nautilus) are still sold and traded around the world with no regulation, oversight, or management. Our prior work in the South Pacific suggested that fisheries significantly deplete Nautilus populations and that all populations are relatively small. In Papua New Guinea, the Nautilus populations were also small while the Allonautilus populations were very, very, very, small. The future of all nautiluses is in jeopardy. As one of our colleagues, Dr. Andrew Dunstan, pointed out during a 2014 Nautilus Experts Workshop, nautiluses are not fished. Rather, they are mined. Nautiluses do not reproduce until reaching 12-15 years of age and only lay around 10 eggs at a time that take one year to hatch. Nautiluses simply cannot produce enough offspring to offset the amount of nautiluses removed from the population. Without regulation of the world-wide trade of nautiluses, they will disappear, forever. Nobody wins at that point.

Deep Sea Mining in Papua New Guinea

In Papua New Guinea specifically, there is another threat. A mining company, ironically called ‘Nautilus Minerals’, will soon begin mining in the backyard of where our team rediscovered Allonautilus. Research around the world is showing just how diverse the biodiversity is in the deep sea and how old and fragile the ecosystem is. But we’ve still only scratched the surface of what lives down there, and perhaps more importantly, how these ecosystems work and their role in the ocean. We know even less about how mining may impact this ecosystem. To think that Nautilus Mining could impact populations of nautiluses is unsettling. At the very least, we need more baseline data of what the deep sea habitat looks like before mining practices continue to spread.

Snap shot of underwater video footage showing Allonautilus and Nautilus again feeding side by side. (Photo by Gregory Jeff Barord)

There is Hope!

There is now a concerted effort to save all nautiluses. It wasn’t started by a government, conservation organization, or scientists. It was started by two 11-year-old boys, who in 2011, read an article in the New York Times and decided they wanted to help. They created the Save the Nautilus Foundation and have since raised well over $20,000 for nautilus conservation research and there is no slowing them down. Besides the fundraising, they have introduced an entire generation of students in the United States, and world, to nautiluses and why they are important. With their inspiration, I created a Facebook page for our work, The Nautilus Files, and learned about an 8-year-old girl who was crazy about nautiluses. A year later, she is now referred to as ‘The Nautilus Girl’ and does everything she can to share the nautilus story and raise money for research.

Back at Central

With the school year underway, a new group of students is learning all about my infatuation with nautiluses. We are one of the few schools in the country, and the world, to actually maintain nautiluses in our laboratory here. By having them here, our students have the unique opportunity to work on research projects that will help save nautiluses in the wild. To think, a 500 million year old lineage could (and will) be saved by the planet’s youngest generation. That’s awesome!

To find out even more about the trip and check out our underwater video footage for the first time, join Dr. Barord on January 13th, 2016 at the Des Moines North Side Library for a presentation titled, “Life in the Slow Lane? Rediscovering the Elusive Fuzzy Nautilus”.